Past Entry of Zippy's Telecom Blog

More Previous Columns

September 28, 2013

The Taxonomy of Happiness, Character, Knowledge and All That

The Taxonomy of Happiness, Character, Knowledge and All That

In the course of curating the 140conf videos for Jeff Pulver's 140 Characters Conference, the problem of categorization reared up as we tried to devise descriptive little tags to insert in the website.

Humans have an innate desire to categorize everything from insects, plants and animals to minerals, words, subatomic particles and human social status. As the philosopher William James said, famously, a baby’s impression of the world is “as one great blooming, buzzing confusion.” To make sense of anything we encounter, our working brains “extract features” of these items and compare these mental “tags” to those of others, thus categorizing the world’s contents so we can deal with them expeditiously.

This can lead to problems: We categorize—nay, stereotype—and immediately “rate” people by their occupation, doling out respect to them accordingly. As the playwright Arthur Miller once said (paraphrasing Karl Marx, as I recall), “Tell me what a man does for a living and I can tell you how he thinks.” Being a systems analyst is a more prestigious occupation than that of a help desk worker, though most people would be hard-pressed to explain what exactly a systems analyst does (aside from charging a lot of money, of course). Today, following Miller’s lead, marketing experts say, “Tell me what a person’s ZIP code is, and I can tell you all of his or her categories: income bracket, likely marital status, likes and dislikes and so forth.”

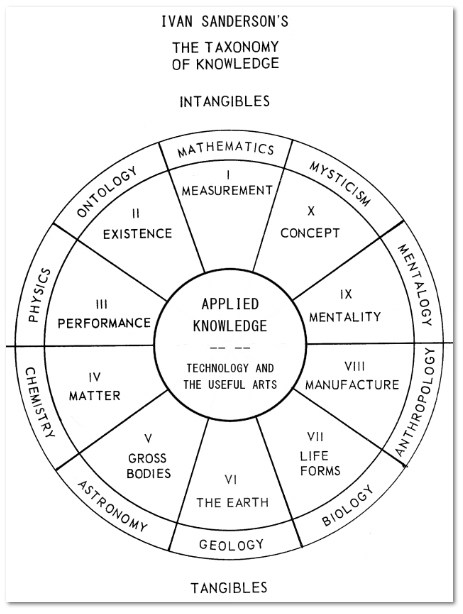

Back in the late 1960s, a long-gone friend of mine, the naturalist and media personality Ivan T. Sanderson (1911–1973), had a fair-sized “Annex Building” on his estate in northern New Jersey that housed his library and collection of curiosities he had collected from around the world. Instead of using the Dewey decimal system or the Library of Congress system to organize his library, he devised his own “Taxonomy of Knowledge,” which took the form of ten principal departments of organized knowledge. Five of these he called “The Intangibles:” Mentalogy (psychology, ethics, aesthetics), Mysticism, Mathematics, Ontology (space, time, locus, cosmology), and Physics. The other five areas of knowledge were “The Tangibles:” Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology, Biology and Anthropology. He arranged these departments in a circular diagram, where an eleventh area, Technologies and the Useful Arts, sat at the center, having access to any or all of the ten major departments of organized knowledge (see illustration).

Sanderson obviously wasn’t the first person to attempt this. For the great 28-volume, 71,818-article Encyclopédie of 18th century France, Jean le Rond d’Alembert and Denis Diderot drew up a tree designed to represent the structure of all human knowledge, a taxonomy inspired by Francis Bacon’s earlier work, The Advancement of Learning. The pair of authors caused a scandal by placing theology in the “Philosophy” category, making it subject to human reason, and not a source of knowledge in and of itself (revelation). They also placed the “Knowledge of God” near “Divination” and “Black Magic” on the diagram, which was a pretty risky thing to do, even during the Enlightenment. Fortunately, no one was burned at the stake for publishing it. (You can see an English translation of the tree of knowledge here.)

Taxonomies also long ago invaded the worlds of sociology and psychology. We pigeon-hole people into race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, educational status and income categories for bureaucratic purposes. (Back in my 1970s college days, I actually had a physical anthropology professor seriously suggest that the categories of the races—Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Australoid, Negroid, Capoid—should each be treated as a subspecies of homo sapiens.) We categorize mental illnesses in psychology’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders(DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association (amusingly, “schizophrenia” for many years was the odd garbage heap category for any bizarre behavior that didn’t fit into any other category).

On the positive side, the lesser-known The Values in Action (VIA) Classification of Strengths is intended to be psychology’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for categorizing and measuring character strengths, focusing on what’s right (not wrong) about people and specifically about the strengths of character that make the good life possible.

As Christopher Peterson and Martin E. P. Seligman wrote about the need for the VIA classification: “After a detour through the hedonism of the 1960s, the narcissism of the 1970s, the materialism of the 1980s, and the apathy of the 1990s, everyone today seems to believe that character is important after all and that the United States is facing a character crisis on many fronts, from the playground to the classroom to the sports arena to the Oval Office to the Hollywood screen. According to a 1999 survey by Public Agenda, adults in the United States cited ‘not learning values’ as the most important problem facing today’s youth. Notably, in the public’s view, drugs and violence trailed the absence of character as pressing problems.”

There is, in fact, a whole VIA Institute on Character, a non-profit organization that systematically explores what is best about human beings.

In case you’re curious, the VIA Classification of Character Strengths is as follows:

Wisdom and Knowledge – Cognitive strengths that entail the acquisition and use of knowledge: Creativity/ingenuity, Curiosity, Judgment, Love of Learning, Perspective (wisdom).

Courage – Emotional strengths that involve the exercise of will to accomplish goals in the face of opposition, external or internal: Bravery (valor), Perseverance (persistence, industriousness), Honesty, (authenticity, integrity),Zest (vitality, enthusiasm, vigor, energy).

Humanity – Interpersonal strengths that involve tending and befriending others: Love (valuing close relations with others, in particular those in which sharing and caring are reciprocated; being close to people), Kindness(generosity, nurturance, care, compassion, altruistic love, “niceness”), Social Intelligence (emotional intelligence, personal intelligence, being aware of the motives and feelings of other people and oneself; knowing what to do to fit into different social situations, knowing what makes other people tick).

Justice – Civic strengths that underlie healthy community life: Teamwork (citizenship, social responsibility, loyalty), Fairness, Leadership.

Temperance – Strengths that protect against excess: Forgiveness, Humility, Prudence, Self-Regulation (self-control).

Transcendence – Strengths that protect against excess: Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence (awe, wonder, “elevation”), Gratitude, Hope (optimism, future-mindedness, future orientation), Humor (playfulness), Spirituality (faith, purpose; having coherent beliefs about the higher purpose and meaning of the universe; knowing where one fits within the larger scheme; having beliefs about the meaning of life that shape conduct and provide comfort).

Some of the categories detailed here have become a research topic in the more prosaic fields of Organizational Behavior (OB) and Human Resource Management (HRM), since an organization is particularly happy and healthy if its employees exhibit altruistic, exemplary behaviors. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), a field developed by Dennis Organ, has been studied with increasing intensity since the late 1970s.

The OCB construct has grown considerably since its initial conceptualization, yet the vast majority of studies done in the area rely upon Organ’s original somewhat pedantic definition: “Individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization.” Organ also created a taxonomy of different behaviors to specify behaviors which were included in OCBs. The taxonomy categorized OCBs into five dimensions: altruism, which is helping behavior aimed at another person (such as helping a sick coworker out), sportsmanship, which is a negative action that an individual refrains from performing (such as complaining about little things), courtesy, which is keeping others informed about what is going on (such as informing subordinates of upcoming changes), civic virtue, which is participation in the political life of the organization (such as attending meetings and keeping informed about organizational decisions), and conscientiousness, which is helping behavior aimed at the organization (such as doing more work than is required for the job).

These behaviors are generally described by researchers in ambiguous terms such as a “readiness to contribute beyond literal contractual obligations” or “behaviors that help units work more efficiently and effectively” or “behavior that contributes to the maintenance and enhancement of the social and psychological context that supports task performance.” Such special or extra-role employee efforts that go above and beyond the call of duty, though not enforceable or even directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system found in capitalist-based businesses, are nevertheless vital qualities that a workforce must possess in order for its organization as a whole to be successful (ironically) in pursuing its own, far different kind of highest good—a ruthless struggle to get ahead of competing organizations.

Bummer!