Ivan T. Sanderson — Epilogue

Let us now move to late December 1973, less than ten months after Ivan’s death.

On passing through Hainesburg I stop briefly to inspect the delapidated, boarded-up remains of Roth’s Inn. A lone farmer heavily bundled in dirty coveralls, with walking stick in hand, unhurridly trudges past my car. For wont of an explanation, I roll down the window and call to him: “Hey there. Pardon me but—what happened to Mr. Roth?”

The elderly gentleman pauses and replies: “He sold out. A couple of new guys are fixin’ up the place. . . Ha! They think they’re gonna turn a profit, but I know better.”

“You don’t think they’ll make money?” I ask.

“Nope. When Ivan Sanderson was around, all of his friends who he didn’t have room for up at his place used to come down here and stay for the night at Roth’s. They’d hang around for a while and have some drinks before they went back up again. When all his friends stopped coming after he died, well, there was no reason for Roth's to stay open."

The sign reading Ivan Road still stands, that small materialization of the reverence held for him by the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside, a sign that has now become enveloped in the branches of a nearby tree, the leaves of which obscure it during the summertime. But right now it is a frosty winter morning, and the tentacled silent guide still faithfully points the way to the local legend’s domain.

I drive into the still vestigial parking lot, get out of my car and walk up a small path of crushed stone that leads to the front patio. I approach the door and knock.

Headquarters is not picayune any more when it comes to making appointments, for fewer people have visited since Ivan’s death.

Sabina comes to the door and opens it. She is wearing a neck brace—arthritis.

I enter the house, seeing before me the kitchen with its long shelves of unfamiliar spices. As I chat with Sabina about old times, I casually walk over to the living room to see if it has retained any of its museum atmosphere. Yes, the “Oriental Room,” as it is called, still lives on, though its decor has been shuffled around and rearranged a bit.

The guest bedrooms beyond are now empty and have been vacant ever since Fred Allsop jetted up from Port-au-Prince in September 1972 to pay final respects to his dying friend.

I finish my chat with Sabina and walk out of the kitchen, past the stairs, and into the room where she had typed out my membership card several years before. Sitting at a desk in the far corner is—Ivan?! No, its only Allen Noe, who has recently grown a goatee that is more Lincolnesque than Sandersonian. He greets me and pecks at a few keys on his partable typewriter.

Upon my mentioning Ivan or any of his past endeavors, Allen sits back and begins to reminisce:

“About ten years ago I was invited to a venison dinner at an establishment up in Massachusetts,” he says. “As soon as I walked into the place I spotted Ivan over at the bar. I went over and introduced myself. He then turned to me and said, ‘So you’re the guy who was born in my bedroom. (Noe had been born in an upstairs bedroom of the Mansion house when his family had owned it at the turn of the century). I want to talk to you, Mr. Noe.’ Well, I had met Ivan briefly several times before, but we had never really talked. We sat at that bar until about 4:00 a.m., talking about life, travel, and just about anything else that came to mind. We had something to eat and then we started in talking again through most of the following day. We saw eye to eye on a lot of things, and we were good friends from then on."

“When we finally did leave that place, Ivan told me that he wanted to plant a weeping willow on his property," says Noe. "As we walked, I reached up an broke off a few branches of a weeping willow that was growing near the parking lot there. I brought them back with us and I planted them out by the swimming pond, over there.” Noe points out the window toward what is now a huge, 60-foot weeping willow tree.

Noe, a retired employee of the Federal Government, was at the time giving freely of his time for Society affairs.

Walking by a shelf, I notice a small black leather photo album labeled "Pix of Meetings." I take it off of the shelf and open it. It is filled with large polaroid color prints of the famous meetings that took place up until a few months before I met Ivan in the summer of 1970. Noe glances over, gets up and joins me.

“I’ve never seen these before,” he exclaims. We work our way through the album, Allen pointing out and affixing names to the various people in the photos. It seems strange to see all of these flurries of activity and amusement captured on a sheet of plastic,.now so many years after the real events have all passed away. There is Ivan, Alma, and a cheerful Marion, alias Sabina. Charming, charismatic people—all of them. And look, a clean shaven Alien Noe—a mere shadow of the man of character whom he now portrays with the help of his new, forceful, and adventurous-looking facial hair.

I look out the window. A flock of guinea hens wanders about the grounds, accompanied by the last two of Ivan’s surviving dogs, Bruno and Marzi. Just then Noe brought out some figures proudly demonstrating that while a few of Ivan’s “fans” had dropped out of the Society after his death, they soon realized, after a few months

of independence, the phenomenal uniqueness of SITU’s library and files. Within these last two months they had all come back and were once again on the membership roll. There were even some new members: One in Australia, two in Yugoslavia, and finally—of all people—the mayor of Albany, New York.

I look out the window. A flock of guinea hens wanders about the grounds, accompanied by the last two of Ivan’s surviving dogs, Bruno and Marzi. Just then Noe brought out some figures proudly demonstrating that while a few of Ivan’s “fans” had dropped out of the Society after his death, they soon realized, after a few months

of independence, the phenomenal uniqueness of SITU’s library and files. Within these last two months they had all come back and were once again on the membership roll. There were even some new members: One in Australia, two in Yugoslavia, and finally—of all people—the mayor of Albany, New York.

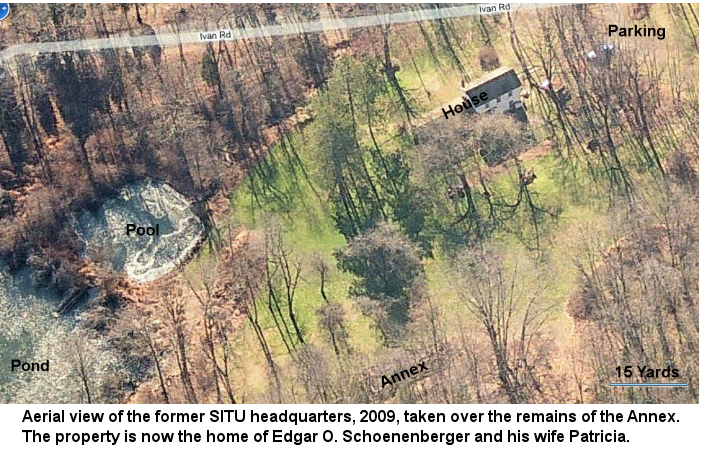

The phone rang. An article was coming in from a Scientific Advisory Board member for Pursuit. Noe once again banged some keys on a Smith-Corona. Things were beginning to hum. He got up and walked over to SITU’s new $1,500 copying machine, busily getting the material to be reproduced in order. He said there were plans to build a $100,000 two-story museum and conference room complex. This was probably the same structure that SITU had discussed building many years before in at one end of the SITU parking lot. It appeared on Eddie Schoenenberger's March 1968 map of SITU headquarters, and architects' plans of this "New Library Building" had been published in the June 1968 issue of Pursuit (incorporating Newsletter No. 3). The structure was never built.

I said goodbye and departed.

Yours truly visited SITU a few more times in the mid-1970s, taking some college chums along for the ride, and to satisfy their own curiosity about my tales concerning Ivan Sanderson and his bizarre scientific society, investigating mysteries just a hair beyond the limits of human knowledge.

We found that most of SITU's files, amazingly, had vanished. As cryptozoologist Loren Coleman wrote in 2007:

One fault of Sanderson’s, however, may have been his trusting of others. As he was getting sicker and sicker with cancer, after Mark A. Hall’s year of being a director of SITU, the end times of SITU in Blairstown, New Jersey, were not happy ones. More and more people, unscreened, would end up coming to visit the Sandersons. Many would “look” at the files, and walk away with materials. By the end, the rumors making the rounds were that people “in station wagons were backing up to the concrete bunker” and loading books and files into their vehicles. The “borrowed” files and books never were returned.

Ivan Sanderson’s concrete building that he had built on his land specifically for his decades of materials was legendary. It was filled to overflowing with files and his priceless library. By the time of his death, the collection of SITU was, more or less, gone.

In a series of contributions and purchases in 1977 and 1983, Ivan's wife Sabina donated his personal papers not in SITU’s library and kept in protected locations, to the American Philosophical Society Library in Philadelphia. This collection of 17,000 items contains diaries, correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, photographs and notebooks, and takes up 27 linear feet of shelf space. She still lives in northern New Jersey, not far from the site of the former SITU headquarters.

With the death of Ivan Sanderson, SITU began a slow but certain death. One of Ivan's friends, the eccentric fortean author John Keel, who wrote the famous book, The Mothman Prophecies, talked about keeping SITU alive—with Keel as its titular head—and "publishing a journal written by Ph.Ds," which in those days was a flight of fancy. That idea went nowhere—Keel was editor of the Society's quarterly journal Pursuit for a few issues, but he apparently changed his mind after realizing the hard work that would be involved, not to mention the fact that such small, unusual, almost cult-like organizations can only galvanize their membership and attract outside resources with the help of a charismatic leader, a quality which the acerbic Keel definitely lacked. (It is perhaps no coincidence that Ivan, in his book This Treasured Land, waxed poetic over architect Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin Fellowship, the ground zero of a "cult of personality" that pretty much became a cult in the literal sense. Ivan may have harbored a small, secret envy of Wright, since nearly all of Ivan's own entourage took advantage of him and then abandoned him when he became seriously ill.)

Moreover, a great deal of in-fighting among the SITU Governing Board was occurring in the wake of Ivan Sanderson's death. That was partly because Ivan, apparently to ensure that SITU would survive one way or another, or perhaps just to please his remaining, loyal friends, took several close associates aside individually and casually told them, "Well, I guess when I die you'll be the one running SITU." The final strange shennigans swirling around Ivan Sanderson extended well beyond the grave: Ivan's friend Bob Durant told me that, after his death, no less than three people showed up with deeds to the property, resulting in a lengthy legal action. After an eight-year court battle during the 1970s and early 1980s, the Sanderson estate and former SITU headquarters was awarded to Ivan's former zoo assistant and partner in the animal business, Edgar O. ("Eddie") Schoenenberger. He lives there today with his wife, the former Patricia Vanatta, another "alumnus" of Ivan Sanderson's Jungle Zoo.

During this time, and aside from the problems with the deed, considerable in-fighting occurred among SITU Governing Board Members and Trustees over what SITU should be doing.

R. Martin Wolf (at left) and Steven Mayne lived at SITU headquarters and were instrumental in keeping the Society operating from 1974 until the end of the decade. Here they are sitting at the conference table in the Annex building, May 1977. (Photo by Richard Grigonis.)

R. Martin Wolf (at left) and Steven Mayne lived at SITU headquarters and were instrumental in keeping the Society operating from 1974 until the end of the decade. Here they are sitting at the conference table in the Annex building, May 1977. (Photo by Richard Grigonis.) R. Martin Wolf and Steven Mayne had occasional "brainstorms" to promote SITU, such as this somewhat cheesy tee-shirt that replaced Ivan's "running doggie" logo with a cross between an question mark and an exclamation point. (Photo by Richard Grigonis.)

R. Martin Wolf and Steven Mayne had occasional "brainstorms" to promote SITU, such as this somewhat cheesy tee-shirt that replaced Ivan's "running doggie" logo with a cross between an question mark and an exclamation point. (Photo by Richard Grigonis.)

A couple of fellows (R. Martin Wolf and Steven Mayne) lived at SITU headquarters and basically ran SITU and helped edit Pursuit during the middle-to-end of the 1970s, then had to leave. More in-fighting occurred around this time, mostly involving a fellow named Robert E. Jones of Byram Township, Sussex County, who had secured a grant from IBM to pay for SITU's photocopier, and who claimed to have had "programmed the Multiple Independently-targetable Reentry Vehicle [MIRV] warheads" for the U.S. military.

After one particularly nasty dispute, Jones dissociated himself from the Society and started his own nonprofit organization in 1976 to investigate unexplained phenomena. Called Vestigia, Jones' group received some considerable publicity starting in December 1976 when they investigated a strange "spook light" that appeared (and still appears) at night bobbling along a wooded stretch of railroad tracks near Long Valley, New Jersey. Yours Truly and my motley crew of college buddies witnessed one of these investigations, and I even wrote up an uncredited short news item about Vestigia's investigations for Science Digest. It was the second article I ever published professionally ("Earth Emits Ghostly Light." Science Digest. July 1982. p. 19.), and I was rather amazed that such a publication was so open-minded as to run an article on the subject. After the death of Bob Jones in October 1991 from heart problems, the group "wound down" a bit, but Peter Jordan and John H. Berkenbush reorganized the group and now continue Bob’s work in investigating the paranormal from a new "Paranormal Research Center" in Wayne, New Jersey. The organization also has a (nearly inactive) "Vestigia group" at Yahoo! Groups.

The supreme irony is that whereas Ivan Sanderson always bragged about how his "scientific society" of SITU would never investigate "intangible" unexplained phenomena such as apparitions, SITU ultimately came under the control of Robert C. Warth of Little Silver, New Jersey, a chemist at Bendix Corporation, a graduate of the University of Rochester, whose original interest was in UFOs but expanded to psychic phenomena and seances (ironically, partly because of an increasingly superstitious Ivan).

During the era following Ivan Sanderson's death, the person who made the single largest financial donation to SITU was cryptozoologist Dale Drinnon ("Ernie" or W. M. Gerald Russell also made a sizable donation). Shortly after Ivan's death he visited the original headquarters while "Sabina W. Sanderson" (the former Marion L. Fawcett) was in residence, and then he stayed for longer periods in the summers of 1975 and 1976, living in the Annex building and spending hours going through the files. Drinnon got to experience Warth's eccentricities firsthand, such as his propensity to have "fits of pique" and tell people he would want nothing more to do with them. As Drinnon later wrote to me in an e-mail, "He [Warth] was sitting on a stack of my submissions for Pursuit for the length of the 1990s and at one point he said he would have nothing more to do with me because he thought I was too chummy with Bernard Heuvelmans." [Drinnon, Dale. E-mail communication. 14 December 2009.]

Under Warth's leadership, SITU's membership shrank dramatically and the Society's quarterly journal, Pursuit, suspended publication in 1989 (my last issue is designated Volume 22, Number 1, Whole No. 85, First Quarter). Still, additional factual material and reports from the remaining members had again accumulated over the years, and the garage and home of Bob and Nancy Warth were overflowing. A small "farmette" of several acres and an allgedly "haunted house" was purchased somewhere near Jackson, New Jersey, as a retirement home. Most of the remaining SITU material was in the garage at the original home in Little Silver, and in two concrete commercial storage comparment areas. A final effort by Warth to revive Pursuit in 1995 was unsuccessful, and SITU continued its decline. Warth died on Halloween, 31 October 2005, from a brain hemorrhage secondary to undiagnosed colon cancer. Nancy Warth now lives at the original Little Silver, New Jersey location.

With the death of Bob Warth, the last remnants of SITU vanished. Shortly after his death, his wife Nancy donated the remaining SITU records, back issues of the Society's journal Pursuit, library, specimens and so forth, to the Society for Scientific Exploration (SSE) , a professional organization of scientists and scholars who study unusual and unexplained phenomena. Founded in 1982, the SSE has about 800 members in 45 countries worldwide and publishes a peer-reviewed journal, the Journal of Scientific Exploration (JSE) and another magazine called EdgeScience, which brings their work to the general public. SSE appears to be a worthy successor to SITU.

Purely in terms of cryptozoology, however, Ivan T. Sanderson himself would most likely be enamored of today's Centre for Fortean Zoology, founded in 1992 by Jonathan Downes (born Portsmouth, England, in 1959) . It is in operation and spirit very much like the old SITU.

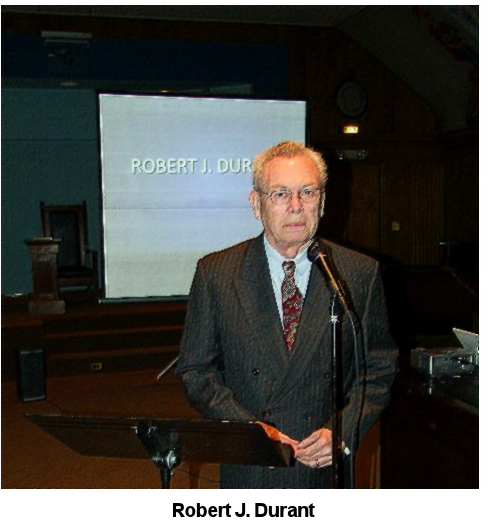

Recollections of Capt. Robert J. Durant

Recollections of Capt. Robert J. Durant

Bob Durant flew helicopters for six years for the U.S. Navy before joining Pan American World Airways. He flew six different types of airliners for Pan Am primarily on international routes serving as navigator, flight engineer, copilot and captain. He was also a flight operations manager for two-and-a-half years supervising 1100 pilots and flight engineers. Bob moved from Pan Am to Delta Airlines in 1991 where he flew until his retirement in 1998. He continues to serve as President of the Pan Am Pilots' Retirement Foundation, Inc.

When Durant, a former Board member of SITU, discovered that Yours Truly was working on this tribute to Ivan Sanderson, he forwarded to me this unpublished recollection he wrote in 2004 (I have added comments in brackets and a bold font where appropriate):

"Remembering Ivan" by Robert J. Durant

It must have been 1968 or 1969 when I first heard the voice of Ivan Sanderson. His accent was a perfect “BBC” upper-class English, but what caught the attention at once—and kept it—was Sanderson’s totally riveting discourse. He was on the Barry Farber radio show, one of the AM powerhouses of the day. And he was talking about the Bermuda Triangle.

I had experienced something that to this day puzzles me, and wanted to let him know about it. While flying in roughly the area of the Triangle, I had observed, from an altitude of some 30,000 feet, a huge mound of seemingly boiling water emerge from the sea about 100 miles north of Puerto Rico. It rose, looking like a gigantic cauliflower, then slowly collapsed back. The diameter of the mound must have been at least one-quarter mile.

So I wrote a letter to Sanderson with those details. To my surprise, he replied with a nice note. Soon we were exchanging more letters. Eventually, I was invited to the Columbia, New Jersey Farm. And thus began a wonderful friendship.

Unfortunately, it was to be a short friendship, because Ivan died in 1973. In fact, by the time I met him, Ivan was already ravaged by various medical problems. He had always had one “bad” eye, and now the remaining eye was deteriorating, so he had to use a magnifying glass to read, slowly scanning, and pausing when it got too much. Before this problem set in, Ivan had been a voracious reader, and he mentioned that it was a real blow to suddenly lose his lifetime habit and joy of vast reading.

But that was just a statement of fact, rather than a complaint. As I got closer to him, I learned that in those final years, sickness and an encroaching blindness were not the sum of his troubles. He was nearly broke, sustained by a few royalty checks that sporadically appeared in the mailbox. [Ivan had run up such large bills with the local grocers that he would offer to pay their income taxes at the end of each year.] And many friends of long-standing, meaning the crowd that clung around him when he made enough money to pay the restaurant and bar bills, and who benefited from his publishing and show business contacts, had stopped calling. I did not learn this from Ivan, but from others. So I could go on at length about the miserable condition in which Ivan’s final years developed. But having stated the facts in outline, I will go on to the more important point. That is, he never really complained. This amazed me, and it is one of my enduring memories of Ivan Sanderson. The man had “character” to a truly exceptional degree.

Ivan was a non-stop talker. But not a bore. Never. This was another exceptional trait. He talked and talked, but the range of topics was huge, and always what he had to say fascinated. And if you want to know how the talking was organized, look at his writing. It was the same flowing, sometimes almost poetic discourse.

His wife Alma died during this period. She was a black woman, a native of Africa, but educated in France [and England, where they met, according to Ivan], and so accomplished that she did translations of French publications into English. Incredibly, they had performed a night club act internationally for many years. They were dancers, doing Latin steps that were still very new. Apparently this was quite a sensation. Ivan said they gave it up because of the rigors of constant travel. Sorry I used the word “incredibly.” With Ivan, just about everything seemed incredible, ridiculous or impossible, but eventually I was able to document nearly every claim he made about his truly amazing life.

He told me that once he was watching a motion picture of a rhinoceros attacking and killing a man. Then he grasped that it was a movie taken of the last moments of the life of—his own father! He knew his father had been killed by a rhinoceros, but had no idea the event had been filmed.

And he was a highly skilled cook, specializing in the food of Southeast Asia. The kitchen was lined with scores of oddly shaped glass bottles, each containing a different spice or vegetable, nearly all of them originating in Thailand, Vietnam or Burma. [As SITU Resident Staff member Richard T. Grybos told me (Richard Grigonis), "Did you ever try Ivan's sukiyaki? He'd make it one day and we would eat it every night for 4 to 5 days."] He told me once that even though he was an experienced naturalist, and had subsisted in the wild for long periods, one thing he would not take a chance on was mushrooms. Apparently he had made a serious mistake once, and was not about to repeat it.

He liked to drink. At the time, I was a pilot with Pan Am, and had a regular run from New York to Ireland, where I would routinely buy one or two bottles of whisky. This was a double-malt called Cardhu, then quite cheap, but now a very expensive brand. To me, the stuff tastes like kerosene, but Ivan pronounced it wonderful, and eagerly awaited my next shipment. That was all I could do for the man, and gladly did it, knowing that he genuinely appreciated the occasional bottle.

It seemed Ivan was always hosting someone at the farm. Some were local farmers who stopped by to chat about entirely mundane things. Others were more exotic. A man with an eye-patch and a strong resemblance to Ernest Hemingway was there often. He was retired from Time Magazine, which he ran for many years, and lived nearby on a luxurious spread, but liked to hang out with Ivan. [Bob Durant is almost certainly referring to Ivan's friend John Stuart Martin, who was part of the original group that started Time, and who was a cousin of its co-founder, Briton Haden. A 1923 Princeton grad, he was nicknamed "the one-armed bandit" because he had lost a left arm in a childhood hunting accident and was resentful of any sympathy, but he could win at games of golf, was a crack shot with a rifle and shotgun, and could hold a telephone using his shoulder and chin while typing and chewing paper clips. He was managing editor at Time (1929–33, 1936–37), and helped to get Life magazine up and running during 1935–36. Like Ivan, however, he was a heavy drinker and was said to be a verbal bully when drunk, a behavior that some say may have blackballed him from being appointed Life's first managing editor. A staunch political conservative, he wrote the narration for the World War II propaganda film, The Fighting Lady (1944) as well as the narration for a filmed version of George Orwell's Animal Farm. Eventually ending up as a freelance writer, he wrote everything from a novel, General Manpower (1938) and Learning to Gun (1963), to The Curious History of the Golf Ball (1968), A Picture History of Eastern Europe (1971), and he was the editor of book, A Picture History of Russia (1945).]

Then there was the big-game hunter from Africa, straight out of Hollywood’s Central Casting, but there to plan strategy for tracking Yetis. And the British aristocrat who lived in a chateau in France, but had taken a week and a transatlantic flight to pick Ivan’s brain about a similar cryptozoological venture. Everyone was treated equally, and Ivan went to pains to ensure that the visitors, regardless of their eminence, met everyone else on even terms.

There was a time when Ivan made a lot of money. His books sold well, and he was a fixture on early television. It was then that, with money in his pocket, he drove from New York City, with nothing other than sightseeing in mind, and found a small farm for sale in the nearly uninhabited western edge of New Jersey. On impulse, he bought it outright. That was a lucky thing, because it was to be his home, headquarters for the Society, and his refuge.

Ivan had his faults. Upon his death, it seems that no less than three individuals produced documents in which Ivan had bequeathed to them the farm! This took considerable sorting out.

Once long ago I was musing about Ivan, and the idea popped into my mind that the best way to describe him in comparison to the rest of mankind is as follows: Ivan was like a color photograph, everyone else was black and white. What a man! [A strangely apt statement, given that Ivan had hosted the world's first color TV series in 1951.]

R. J. Durant

March 1, 2004

Special Thanks to Richard T. and Linda Grybos

Special Thanks to Richard T. and Linda Grybos

Former SITU Resident Staff member Richard T. Grybos was kind enough to send Yours Truly many transparencies, back issues of SITU's journal, Pursuit and various SITU newsletters, occasional papers, minutes of meetings, annual reports, etc. He also has provided considerable email correspondence and has made himself available for interviews concerning Ivan Sanderson and those who were in his orbit. His (now ex-) wife, a superlative genealogist, has recently become fascinated with the story of Ivan Sanderson and has traced the Sanderson family tree back several generations—her research is also in the process of being incorporated into this website. I thank them both for their earnest contributions in time and effort in assisting me in the creation of this tribute to Ivan Sanderson.

Yours Truly (Richard Grigonis) hopes that you have enjoyed this tour of the extraordinary life of Ivan T. Sanderson. And, unlike a conventional printed biography, this is a perpetual work in progress. If anyone out there reading this ever met him, knows of any anecdotes about him, or has stumbled across any interesting old newsclippings concerning him, please send me an e-mail at